Comprehension Skills or Strategies - The Masked Confusion

What’s

the difference between comprehension

skills

and comprehension strategies? Are they synonyms or do we teach different things

when we are teaching them?

Comprehension

skills and comprehension strategies are very different things.

They

are often confused; the terms are often used interchangeably by those who don’t

understand or appreciate the distinctions they carry.

And,

most importantly, these concepts energize different kinds of teaching

altogether.

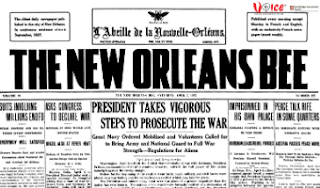

The

older of the two terms is “reading comprehension skills.” It was used

occasionally throughout the Twentieth Century, but really took off in a big way

in the 1950s. Professional development texts and basal readers were replete

with the term and its use burgeoned for a span of three decades before

slackening a bit.

“Comprehension

strategies” were rarely heard of until the 1970s. The term was much in use

throughout the 1980s, both because of the extensive strategy research and

because those promoting comprehension skills appropriated the newer, trendier

label- Like old wine in new bottles.

Use

of the term strategies finally overtook skills in 2000, but not necessarily

because the practices of teachers actually had changed.

Basically,

the term comprehension skills tend to refer to the abilities required to answer

particular kinds of comprehension questions. Skills would include things like

identifying the main idea, recognizing supporting details, drawing conclusions,

differencing, comparing and contrasting, evaluating critically, knowing

vocabulary meaning, and sequencing events.

The

old basal readers would make sure that students got plenty of practice with

particular comprehension skills ensuring they practiced answering particular

kinds of questions.

Of

late, the core reading programs do pretty much the same thing with the

educational standards, with each standard being translated into a question type

in lessons and assessments.

For

most of these skills, there are no studies showing that they can be taught in a

way that leads to higher comprehension, and even in those few instances where

there is such evidence, the effects are quite minimal .This is probably due to

greater attention to reading the text than to practicing the so-called

“skills."

In

fact, there have been a number of studies and logical analyses showing that

these skills lack any kind of psychological reality. They are indistinguishable

from one another in test performance, though that hasn’t stopped instructional

designers from trying to come up with programs that would teach these skills in

a way that would benefit achievement.

There

has been a lot of research into question types over the past 50-60 years.

Despite the claims, this body of research is a morass. There are numerous

variables that may be affecting any of these results that it would be

impossible to distinctly know what it all means.

Reading

has much more to do with being able to read particular kinds of texts and to

deal with particular kinds of text features than to answer particular kinds of

questions. The common belief is that if texts were easy, students could answer

any kinds of question about them, while with sufficiently complex texts, they

couldn’t answer any question types, no matter how simple.

Each text presents information in its own way,

and reading comprehension is heavily bound up in the readers’ knowledge of the

topic covered by the text. As such reading comprehension (different than

decoding) is not a skilled activity, per se.

If

comprehension is not a skill, then why has that been such a popular way to

teach it? Initially, the concept fit the times. In the late 1950s when it

“broke out,” B.F. Skinner’s version of behavioural psychology (e.g.,

stimulus-response, programmed learning) was in vogue. The idea that learning

would result if we could simply induce particular responses to questions and

then reward kids for their answers-rinse and repeat-seemed very convincing.

It

has been harder to eradicate than a fungus, because it appears to map onto

educational standards and the high-stakes tests. Principals and teachers assume

it makes sense to practice the “comprehension skills” that tripped the kids up

on the tests. So, they “use their data”: combing through test results to

identify the kinds of questions that students failed on and then practicing

those supposed skills over and over in the hopes the students will be enabled

to answer such questions on the next test.

Sadly, that it hasn’t actually worked doesn’t seem to dissuade them at

all.

The

basic premise of strategies is that readers need to actively think about the

ideas in text if they are going to understand. And, since determining how to

think about a text involves choices, strategies are tied up in meta-cognition

(that is, thinking about thinking).

Comprehension

strategies are not about coming up with answers to particular kinds of

questions, but they describe actions that may help a reader to figure out and

remember the information from a text.

For

example, the idea of the summarization strategy is that readers should stop

occasionally during reading to sum up what an author has said up to that point.

Doing that throughout a reading and at the end has been found to increase

recall… recall in general, not of any particular type of information.

Another

frequently studied comprehension strategy is questioning. Students read,

stopping throughout to quiz themselves on what the text says (and going back

and rereading if one’s questions can’t be answered). The point isn’t to ask

particular kinds of questions, so much as to think about the content more

thoroughly, more actively than one would do if they just read from the first

word to the last.

These

kinds of actions-these strategies-are used intentionally by readers to increase

the chances of understanding or remembering what one has read.

Comprehension

strategies need to be practiced too; however, they aren’t learned by repetition

and reinforcement, but by gradual release of responsibility (including modelling,

explanation, and guided practice).

On

the other hand, there are very good reasons for teaching comprehension

strategies, but there are at least three big problems with that kind of

teaching.

First,

studies of comprehension strategies have tended to be brief, usually about 6

weeks in duration (there are exceptions). Somehow that has been translated into

substantial amounts of strategy teaching across students’ school lives. To be

perfectly honest, no one, including me, knows how much strategy instruction is

needed. But there is certainly no evidence that there are benefits to be

derived from 8 to 10 years of 30-35 weeks of strategy teaching.

Second,

the only point to using strategies is to make sense of texts that couldn't be

grasped without that effort. Many texts are easy enough that a reader would not

need to expend that amount of energy in comprehending. Unfortunately, most

strategy instruction that I have seen takes place in texts that frankly are

relatively easy for the students to read. That means they have to pretend to

apply those strategies in situations that wouldn’t benefit from such effort. If

students ever do apply these strategies to complex text, they are usually on

their own. Most skip the effort since what such teaching conveys is that you

don’t need strategies.

Finally,

even major proponents of explicit comprehension strategy instruction argued

that as important as it was to teach strategies, teachers needed-even when

teaching them-to make sure the students were actually learning the text content

and not just the strategies they were using to think about that content. That

principle largely has been ignored by teachers and Educators.

Comments

Post a Comment